Persian Rugs Guide

All the carpets and rugs that are weaved in Iran are based on the models and traditions inherited through generations by Persian weaver

Persian rugs have the scent of dreams and feel silky like dark blue oriental nights. Drenched in the colors of the evening sun in the deserts of Iran, gardens full of flowers, animals and other symbols, they carry poetic appeal, artful sophistication and intellectual simplicity that are the main characteristics of Persian people and their culture. Love for life and everything that is beautiful, pure and humble and most of all, knowledge and gratitude for the gift of living, these are what genius carpet weavers have encrypted in colorful patterns.

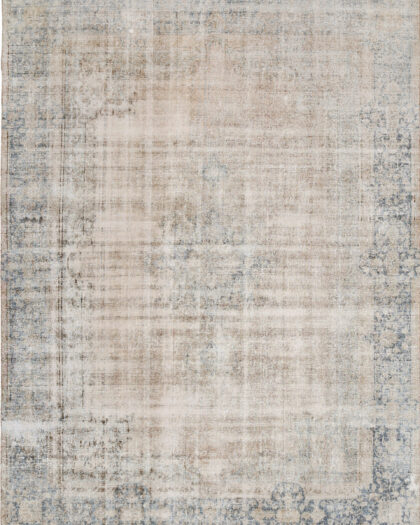

- $900.00

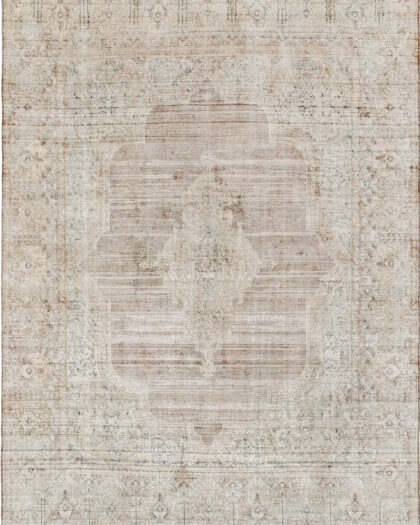

- $950.00

- $645.00

Persian carpets can be categorized in many groups depending in the city or area where they are produced. Hence, they are named after the name of the city in which they were weaved or after the name of the tribe that makes them. Carpets and rugs made by Iranian weavers consist of fascinating artworks that enclose patterns, pure design, soft and serene elements instead of flashy colors. The areas that are famous for the production of some of the most beautiful carpets are Isfahan, Shiraz, Kerman, Kashan, Herat, Teheran, Shushtar, etc.

Main Themes and Symbols of Iranian Carpets

Gardens, flowers, medallions, and animals are the main themes of the carpets weaved in Iran. At least, this how experts divide them. Such elements are used even in architecture, monuments, fountains and book covers. There are cases when they are completely abstract and many and cases when they aren’t. Strong and powerful emotions are expressed through those elements. In other words, such carpets make the earliest and most real form of abstract art. Carpets are deep and quiet at the same moment and make a great place where one can dream.

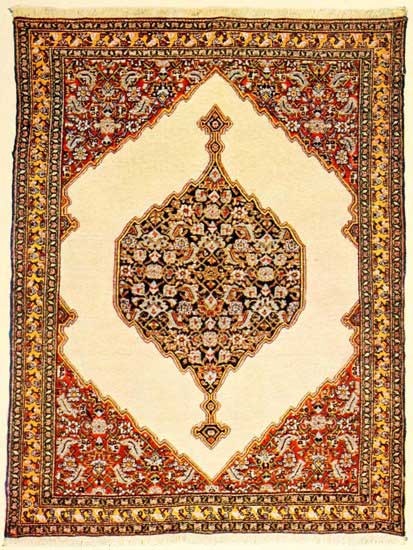

Symmetry is an essential principle as it reflects the balance in everything. Moreover, symmetry makes easier the organization of the pattern. Although it can happen that some rugs have a similar design, there are no two identic hand-knotted carpets in this world. Some carpets have a central medallion and other floral designs while others may have symbols and motifs related to animals and flowers. Some of the most used are the peacock, the tree of life, lily, lotus, iris, the paradise bird, pomegranates, the comb, stars, and numbers.

Meanwhile, even colors have their meanings. Blue means power force and solitude, red means beauty, wealth, luck, courage, faith and joy, green is the holy color of the prophet, white means purity, gold means power, brown means fertility and yellow is related to the sun and joy of life.

The combination of all these elements needs great skills and it can be made only by talented weavers who use natural dyes and the best wool. This explains why rugs made in Iran are so expensive and highly desired by individuals, art collectors, and museums. An Iranian rug is not only a precious item for home décor. It communicates an entire culture through symbols and colors.

Antique Persian Rugs

Thinking that carpet weaving mastery has been solely related to the combination of the right designs and patterns by skilled artisans would be childish. Those who can look deeper know that ancient carpets were made based on a language of symbols and visual aesthetics that gave a touch of personalized individuality to every knot. They are like a portal straight to the thoughts and wishes of the weaver.

There are many commonly used elements like colors and symbols in ancient Persian Rugs that make good storytelling elements and complete the whole idea of the weaver. They help to define if the weaver has depicted personal information or a story from the past. Although it cannot be compared to higher intellectual forms of artistic expression, those rugs helped to enrich Oriental and Western cultures with elements of mysterious beauty. Mystique elements in most forms of applied oriental arts are linked to their tales, beliefs and needs.

One of them is the garden, floral designs, gardens and animals. It is normal that a country where water is so important depicts images of beautiful gardens almost in every form of art and decoration. Other symbolical elements included in these rugs are animals and colors. Each of them is used to represent a single emotion or character, while combined together they can create a whole story.

The most common used creatures and their meanings:

Dragon – emperor

Phoenix – empress, immortality

Camel – wealth, happiness

Lion – victory, power

The eagle in flight – good fortune

The resting eagle – the high-mindedness of the spirit

Bat – happiness

Dog – protector of noble places

Hunting dog – glory and honor

The tree of life – understanding, truth

The sun – radiant light, lucidity

Duck – faithful marriage

Dove – peace

Tarantula – prevents from bad luck

Stag – long life

Fish – undying love

Cypress tree – life after death

Persian artisans from Tabriz, Isfahan, Kashan and Kerman weaved some of the most astounding designs through the combination of the above-mentioned symbols. Nowadays these symbols are not used in the same way they were in ancient time. However, nomad weavers continue to knot what they see, landscapes and other motifs related to their personal experiences. Meanwhile, weavers in villages focus on designs and motifs that they are asked to use.

From the book: The Oriental Rug by William De Lancey Ellwanger

Chapter V: OF PERSIAN RUGS, SPECIFICALLY

To describe in detail the characteristics of all the classes of rugs and carpets that have been mentioned would be hardly possible, even with a hundred object lessons. The peculiar features of some of them, however, may be noted. But first be it observed that the term “antique” as applied to rugs is generally sadly abused. A rug is not beautiful simply because it is old. It must have been fine when new, it must have been carefully preserved, and it must rejoice in a ripe old age. Time must have dealt kindly with it, and only softened and mellowed its original beauties. Let the antiques which are but rags and tatters, however valuable for their design, hang in the [Pg 44]museums, where they belong! The only merit of one of these genuine remnants of three or four centuries ago is in their originality of design. They were creations and not imitations, and made by true artists and not merely skilled weavers. Choose you, instead, a more modern rug of fine quality which will improve from year to year as long as you may live to enjoy it.

It may also be premised that the sizes of rugs run from about three feet to six feet wide by four to ten feet long. Few rugs approach squareness, and rugs wider than seven or eight feet are classed as carpets.

Some of the most beautiful pieces used to come, and still do, in the form of “strips,” “hall rugs,” or “stair rugs,” according to trade parlance. They are worthy of a better name, which is their Persian term, “Kinari.” They were made in pairs to complete the carpeting of a Persian room, being placed on either side of a centre rug, with two shorter strips at the top and [Pg 45]bottom. More fine specimens of these long strips are now to be found than of smaller sizes, and they should not be neglected by the collector. By artistic arrangement and device they will accommodate themselves to almost any house, somewhere, and few choicer prizes can be bought to-day.

The Persians are eminently the best rugs to buy. They are usually finer and more closely woven than the others, and more graceful in design, and seem to show a more refined and aristocratic art. The Kirmans would be the first choice, and are to the rug dealer what diamonds are to the jeweller, a staple article which he must keep in stock, and which finds a ready sale. But even were it possible to buy a true diamond Kirman, the very catholicity of taste to which diamonds and Kirmans appeal detract from their merit in the eyes of those who seek for more individuality. For the new Kirmans, fine, soft, and clean as they look, are all very much alike, and mostly[Pg 46] copies or variations of a few particular antique forms, with a floriated medallion in the centre, or a full floriated panel, and floriated corners. A familiar design is a vase of flowers in graceful spread, with birds perching on the sprays. Or, again, they show some adaptation of “the tree of life.” This symbolical figure appears in many forms, now denuded of its leaves like the “barren fig tree,” and covering the whole rug, and now in smaller form as “the cypress tree,” or the sacred “cocos,” three or more to each rug, in full foliage and looking for all the world like certain wooden fir trees. It needs only the combination of these trees with the stiff wooden animals, far more wonderful than Noah ever knew, and tiny human figures, which might be Shem, Ham, and Japhet, all of which adorn these rugs, to remind one of the Noah’s ark of childhood. Representations of birds, men, and animals never appear on Turkish rugs, the explanation being that the Turks, as Sunna Mohammedans, the orthodox sect, are opposed to them on religious grounds; while the Shiites, the prevailing sect in Persia, have no such scruples.

But before leaving the subject of the Kirmans, be it well understood, by the wise and prudent, that not one out of a thousand, or indeed ten thousand, of those on the market to-day (and they are as common as door-mats) has any pretence to genuineness. They are faked in every way. They are washed with chemicals to give them their soft colourings, they are made by wholesale and, it is said, in part by machinery, and they are no more an Oriental rug than is a roll of Brussels carpet or an admitted New Jersey product. To the credit of whom it may concern, it must be stated that the dipping, washing, and artificial aging of these commercial pieces is mostly done by cunning adepts in Persia before their works of art are exported. Only an expert’s advice should be relied on in buying a Kirman, to-day, and even that should have a good[Pg 48] endorser. The distinction between Kirmans and Kirmanshahs was founded in fact and was important. But the latter term as now used in the trade is only poetical. It is the same new Kirman euphemized. No other rugs except silk rugs, which come under the same ban, have proved such a profitable swindle to unscrupulous and ignorant vendors, and have given a bad name to the dealers who try to be honest in their calling.

The Sehnas are highly prized by the Orientals and Occidentals. Old examples are uncommon and are very choice. “Their fabric gives to the touch the sense of frosted velvet. They reveal the Meissoniers of Oriental art,” says a writer on the subject. Some of these come in very small sizes, like mats, two feet by three. They have a diamond design, the centre being a graceful floriated medallion on a background of cream, yellow, red, or green, with floriation at the corners, making the diamond. They are the most exquisite of[Pg 49] Persian gems, and are further considered in another chapter.

The Sehnas have the nap cut very close, wellnigh to the warp, and are therefore often too thin for utility. They do not lie well on the floor, and by reason of their short nap look cold and lack richness and lustre. If you can find a choice one, however, and if, happily, as sometimes occurs, it may have a little depth of nap, you will own a pearl of great price.

The Khorassans are very soft and thick. They generally show the palm-leaf or loop design in their borders, and are altogether desirable. Their colouring almost always inclines to magenta, but time subdues this to a delicate rose. Time has also subdued most of the specimens offered, to the sad detriment of their edges and ends. The ends are very seldom perfect, and age seems to bite into the borders of the Khorassans with a strange and voracious appetite. It is well to consider these defects in your choosing.

The Serabends and their class have one border peculiar to themselves and a centre of double, triple, or multiple diamonds in outline, in which are scattered irregular rows of small figures, generally palm leaves, so called. This peculiar figure has three or four different names, the palm leaf, the pear, the loop, etc. It was originally worked into the fabric of the finest Cashmere shawls, and represents the loop which the river Indus makes on the vast plain in upper Cashmere, as seen from the mosque there, to which thousands made their pilgrimage. It was thus intended as a most sacred symbol and reminder. The Serabends are firm in texture, lie well, and are most satisfactory. Sometimes, however, the green in them shows the faults of an aniline dye. Their designs are peculiar to themselves, but never become monotonous. The palm-leaf pattern is of course common to many kinds of rugs. But the varieties in the form and size of it are infinite.

The Shiraz rugs are warm in colour, lustrous, but rather loosely woven. Many of them show the “shawl pattern,” small horizontal or diagonal stripes. These striped rugs, however, are always wavering and irregular in design and soon tire the eye. They are well passed by. Reproductions of the old Shiraz designs with the centre field filled with innumerable odd, small figures used to be common a few years ago. They were very rich and handsome. Almost all of them, however, have the great defect of being crooked. They will puff up here or there, and, pat, pull, or pet them as you may, it is hopeless to try to straighten them. They are frequently called Mecca rugs, on the generally accepted statement that these are the rugs usually chosen to make the pilgrimage to that shrine.

The Youraghans and Joshghans (Tjoshghans) possess the general excellences of the best Persians, but they are not commonly seen. The Joshghans will show in their field a light lattice-work design with conventionalized roses, or graceful diaperings and patternings, of the four-petalled or six-petalled rose. The Persian rose is single, of course, and appears in many simple forms. The Joshghans might be the prototypes of some of the old Kubas or Kabistans, except that floriation was replaced by tiling and mosaic work in the Daghestan region.

The Feraghans are not as finely woven as the Serabends, and on that account, primarily, yield to them in excellence. But old Feraghans often come in smaller sizes than the Serabends and in more desirable proportions. On the other hand, while Feraghans are generally of a firmer quality, there are also antique Serabends heavy and silky. Between the two it would be little more than to choose the better specimen. While the Feraghans have no accepted border to distinguish them, they have a most marked characteristic in the decoration of the field. It is[Pg 53] a figure like a crescent, toothed inside; it might be a segment of a melon. But more than likely it was originally a curled-up rose leaf; for the rose, variously conventionalized, is most common to this class. There is generally an indication of a trellis, on which the roses are formally spread. But the curled leaf is almost always in evidence, however varied or angular it may be drawn.

The Persian Mousuls are perhaps the best rugs now to be had for moderate prices. The region where they are made, being partly Turkish and partly Persian, gives them some of the characteristics of each nation. But the choice ones are always offered as Persian; and the designs of most of them are distinctively of that country, with frequent use of Serabend borders, Feraghan figures, etc. Their centre field sometimes contains bold medallions, but generally it is filled with palm-leaf or similar small designs, which[Pg 54] in themselves are quite monotonous, except as they are diversified and made beautiful by graduated changes of colour in both the figures and background. Sometimes these streaks of varying colour make too strong a contrast, but generally they shade into each other most harmoniously, and, the nap being heavy and the wool fine, these rugs are eminently lustrous and silky. They have no rivals in this regard except among the Beluchistans and treasured Kazaks. As you walk around them they glow in lights and shades like a Cabochon emerald. One of their distinguishing designs is a very conventionalized cluster of four roses, the whole figure being about the bigness of a small hand. There is a rose at top and bottom and one on either side, with conventionalized leaves to give grace. The design is recognizable at a glance, and is wellnigh as old as Persia. For the rose is conceded to be Oriental in origin, and if it is not primarily a Persian flower, it belongs surely to her by virtue of first adoption.

The designation of certain rugs as Kurdish or Kurdistan has been used indiscriminately, yet they are by no means the same, and between the two classes is a well-marked distinction which should be recognized. Kurdistan is a large province in northern Persia, with a protectorate government both Turkish and Persian, and with the Turkish inhabitants in the ratio of about two to one, according to the geographers. The Kurds constitute only a small but most important part of the population. They are generally spoken of as “a nomadic tribe,” or more frequently as “that band of robbers, the Kurds.” Regardless, however, of their morals or habits, by them are made [Pg 56]characteristic, coarse, strong, and often superb rugs which are properly called “Kurdish.” On the other hand, the Persians in Kurdistan make a finer class of rugs and carpets, which are known as Kurdistans. These latter have been praised by an eminent authority as “the best rugs now made in Persia and perhaps in the East.” They are certainly bold and splendid in design, beautiful in colouring, and of great strength and durability.

The Gulistans are thick, heavy, and handsome, with striking designs, frequently like the flukes of an anchor, on a light ground. They are not common now even in modern weaving.

There are many other Persian rugs which might be further specialized and considered. But such old commercial names as Teheran, Ispahan, etc., can in fact only be differentiated by an expert; and when experts disagree, as will frequently occur, and when they are at a loss to decide whether an important specimen is an Ispahan or a Joshghan, classification becomes obscure to the layman and even to the collector; and he will wisely avoid the complexities of such discussion. So, also, Sarak rugs are rarely seen now save in modern reproductions, and must be passed by with the same criticisms as apply to the new-made Tabriz.