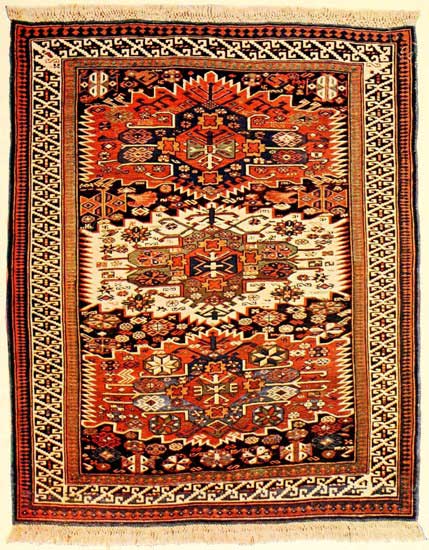

CAUCASIAN RUGS, DAGHESTAN AND RUSSIAN TYPES

Chapter VI – The Oriental Rug by William De Lancey Ellwanger

The Daghestan rugs of Caucasia are only second in importance to those from Persian looms. An opinion is reserved, nevertheless, regarding antique Turkish weaves, which are hereinafter considered.

If history does not satisfactorily prove that the Caucasus was originally the northern part of Persia (as may have been, under Cyrus), Persian dominance and influence may be demonstrated, in textile art, by rug borders, patterns, and designs. The Shirvans, Kabistans, Chichis, Darbends, Karabaghs, all exhibit pronounced Persian characteristics, and show the educational power of the mother country of this handicraft. Fineness of weave, delicacy of hue, and chaste simplicity of design are distinguishing features of this group. But, as contrasted with the Persian patterns, the Persians use for their detail roses, flowers, palm leaves, etc., while the Caucasians gain similar effects from geometrical figures, angles, stars, squares, and hexagons, with small tilings, mosaics, and trellisings. The true and the beautiful was never better demonstrated by Euclid through angle, square, or hypothenuse. An old Chichi rug, like a drawing of Tenniel’s, will prove what grace may come without a curve and by angles only.

It is unfortunate that the best rugs of the Caucasus come from the large province of Daghestan, and that that general term is applied to them indiscriminately. Twenty or more years ago most of the Oriental rugs which were sold here to an uneducated and unappreciative public came by way of Tiflis, and for lack of knowledge were all branded with the common name of Daghestan. Thousands of beautiful Kabistans, Shirvans, Bakus, etc., were then sold for a song under the one arbitrary title. They would be priceless to-day, and yet the former commercial, vulgar use of the name leaves it in undeserved disrepute. As used in this chapter, it is intended to mark a distinction between certain of the Caucasian types, which it properly represents, and the Russian types from the same region, which are illustrated in the Kazaks and Yourucks.

Size: 4.5 x 5.6

What may have become of all the fine Kabistans, which were forced upon the market years ago, is a question. Are they all worn to rags and lost to the world? Or do they still turn up at chance household auctions? Many fine specimens may be so discovered, dirty, disguised, and disreputable, but easily reclaimable and made anew by washing. There is a theory, also, that many choice pieces came to San Francisco in the ’seventies and ’eighties, and are lost to sight and memory somewhere in [Pg 64]California. A collector might well explore this home field.

Too great praise cannot be given to the old Shirvans, with their “palace” or “sunburst” pattern; to the Chichis, with their mosaic work, worthy of Saint Mark’s Cathedral; to the Karabaghs, with their flaming reds; or to the Kabistans, with their soft, light tones of colour, made softer still in contrast with ivory and creamy white. These are the despised Daghestans which were, and for which the collector may now vainly search abroad.

It is not always easy to distinguish between an old—or middle-aged, may we say?—Shirvan or Kabistan. Many of their designs are common property, and it is the cleverer weaver who executes them the better. This broad statement may be made by way of a test: the best of the Shirvans are rather loosely woven and thin. The Kabistans are of finer weave, are firmer and heavier, and lie truer on the floor.

Two classes of rugs from the Caucasus have been referred to as Russian, the Yourucks and Kazaks. There is no authority for the distinction except in the rugs themselves. They prove their case from their thickness and iron durability, from their sombre or strong red colouring, and from their daring crude and simple designs. In their utility they bespeak an article of warmth and weight, and in their art they represent a barbaric simplicity like a Navajo blanket. Kazak and Cossack are almost synonymous terms; and the Cossacks, the Kurds, and the Indians have something of kinship in weaving, at least. But the Kazak rugs are not all crude, by any manner of means. If strength is their first characteristic and strong primitive pigments in rare greens, reds, and blues; and if their patterns are simple and angular;—none the less, in antique specimens, much originality was shown in the drawing of their borders, and soft browns and yellows with ivory white appeared in their colouring.

Of the Shirvans, Chichis, etc., ordinarily offered, there is nothing to be said. They are cheaply and roughly woven, and made only to sell. They are disposed of by the thousands at auctions, and piles and piles of them fill the carpet and department stores. Be it said to their credit that they will outwear any machine-made floor covering; that they are good to hide a hole in an old carpet; that they help to furnish the bedrooms of a summer cottage; that they are most useful in the back hall; and, in fine, that they are better than no rugs at all. Yet, on the other hand, be it well understood that they are not, as frequently advertised, “exquisite examples of textile art,” and that fine Oriental rugs are not to be bought at “$6.98”* apiece.

*This is from a book written in the early 1900