Turkmen carpet weaving is linked to the geography and history of this country. The Turkmen people had woven carpets for centuries and they were divided and named after specific tribes. Turkmen tribal groups that lived in the west part of the country: Chodor, Goklen and Yomut; tribes that lived in the east: Tekke, Salor, Saryq; and tribes that lived in the north: Ersari were known for the production of good quality rugs.

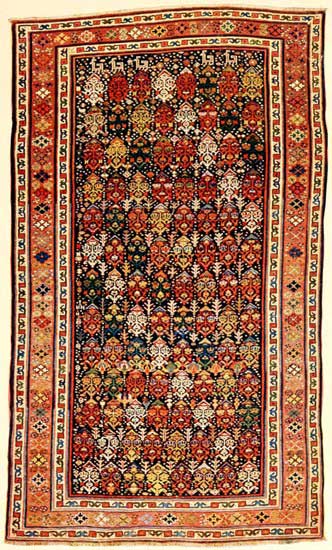

All these tribes have weaved carpets for floor covering and other purposes and their quality rated from good to excellent. Their main motif that make Turkmen different from other oriental carpet in the gul. With the exception of rugs made by the Ersari tribe, all the others have this geometric motifs that stands for a flower. Guls of different sizes and shapes are combined together. The geometric gul and the red-brown palette are typical elements of Turkmen carpets.

The Weaving Techniques of Turkmen Carpets

Turkmen weavers employ various knotting techniques, with the asymmetric (or Persian) knot being predominant. This method allows for the creation of highly detailed patterns, contributing to the dense and durable texture of the carpets. The choice of knot, along with the type of wool and dye used, significantly influences the texture, color richness, and longevity of the carpet, distinguishing the work of different tribes even further.

The Cultural Significance of Turkmen Carpets

In Turkmen society, carpets are more than just floor coverings or decorative items; they are integral to the social fabric. They are used in ceremonies, as dowries, and as symbols of status and hospitality. This cultural significance is deeply intertwined with the craftsmanship and aesthetic qualities of the carpets, reflecting the community’s values and traditions.

They are made with wool or goat hair and the knotting technique differs from one tribe to another. There are the Ersari rugs, which have no typical tribal element, but seem to merge motifs from Chinese and Persian designs and colors that other Turkmens don’t use. Just like Ersari, even Salor rugs feature colors and structural differences that are unusual in other Turkmen carpets.

Carpets by Salor tribes share some common characteristics with Tekke tribes. Their name is related to well-known Bokhara or Bukhara rugs. The designs of these rugs are the result of a mixture of Persian, Pakistani and Afghani designs. They are the most famous of all Turkmen rugs.

Nomadic carpet weaving in Turkmenistan changed not for good during the 19th century when war and conflicts caused increased poverty. Therefore, this craft became commercialized. Carpet weaving turned into a source of income and weavers adapted their designs and colors conforming to the foreign market demand. It was also the period when the use of synthetic dyes thrived. Meanwhile, political changes induced people that the concept of nomadic life had no place in Turkmenistan. Rugs and carpets weaved after the revolution were all produced in state-owned workshops.

The Revival of Traditional Techniques

Despite the challenges faced in the 19th and 20th centuries, there has been a resurgence in the traditional methods of carpet weaving among the Turkmen people. Artisans are increasingly returning to natural dyes and hand-spinning techniques, striving to recapture the authentic beauty and quality of their ancestral crafts. This revival is not just about preserving a cultural heritage; it’s also about re-establishing the Turkmen carpet’s status in the global market as a luxury item known for its unparalleled craftsmanship.

Collecting Turkmen Carpets

For collectors and enthusiasts, Turkmen carpets are prized for their historical and artistic value. Identifying a genuine antique Turkmen carpet involves examining its weave, color, and patterns, with a particular focus on the clarity of the guls and the harmony of the natural dyes. As the market for these carpets becomes more sophisticated, understanding their provenance and the characteristics of different tribal styles has become paramount for collectors.

Currently, Turkmens take their rugs very seriously. They have the Ministry of Carpets, which focuses on the preservation of hand-weaving traditions. When one wants to buy a carpet in Turkmenistan, he or she has to prepare a lot of documents that clarify: the age, region of origin, the materials used in it, the name of the merchant, the day when it has been purchased, and provide documentations from the Ministry of Carpets that gives the approval for taking the carpet out of Turkmenistan.

Conclusion

Turkmen carpets represent a fascinating intersection of art, culture, and history. Their enduring appeal lies in their complex patterns, vibrant colors, and the skillful craftsmanship that has been passed down through generations. As symbols of identity and tradition, these carpets continue to captivate and inspire, offering a window into the soul of Turkmenistan.

FAQs About Turkmen Carpets

- How can I tell if a Turkmen carpet is authentic? Authenticity can be gauged by the carpet’s material, knot density, pattern intricacy, and the natural variation in its dyes.

- What makes Turkmen carpets unique compared to other Oriental rugs? Their unique gul motifs, deep historical roots, and the specific weaving techniques of the Turkmen tribes set them apart.

- How should I care for my Turkmen carpet? Regular vacuuming, avoiding direct sunlight, and professional cleaning are essential to preserve the carpet’s vibrant colors and intricate patterns.

- Can Turkmen carpets be used in contemporary interiors? Absolutely. Their timeless beauty and rich textures can add depth and character to modern and traditional settings alike.

The Oriental Rug by William De Lancey Ellwanger

TURKOMAN OR TURKESTAN RUGS

Chapter VIII

The geography of the carpets and rugs thus far considered has included a very considerable area.

Any traveller or collector who may have journeyed in fact to the regions where they are made may well have stories to tell, for his wanderings will have led him into strange lands and wild places.

But the remaining classes of rugs, which we are wont to see lying gracefully in front of our hearths, as tame and peaceful as kittens, have come from still farther and wilder regions of the world; and the wonder is that we see them at all or are permitted the privilege of treading on them. The Turkestan class, so far as our subject is concerned, carries us east from Persia,[Pg 80] through Afghanistan and Beluchistan even into China. They are Oriental in very truth, and at first blush, it would seem, should be more crude and barbaric in their art. But as compared with the bold, rough, and rude weaves and patterns of the Russian Caucasians, they are, as a class, most refined and delicate in design and fine in texture.

It has been said that “whoever has seen one Bokhara rug has seen them all.” Their set designs and staple colouring have been so long familiar that we have lost respect for them. There are the well-known geometric figures for the centre, smaller similar figures for the borders, and a mosaic of diamonds or delicate traceries of branches for the ends. Choice examples, like the stars, differ from one another in glory only. The variations evolved from the one conventional design are almost infinite; and the many shades and tones of red which are used bring to mind the paintings of Vibert and his wonderful palette of scarlets, carmines, crimsons, maroons, and vermilions.

Some of the rare old Bokharas come in lovely browns and are almost priceless in value. Sad to say, it remained for an American vandal to discover a process of “dipping” or “washing” an ordinary rug so as to imitate these rare originals, and many dealers unblushingly sell these frauds. To wear imitation jewelry is far less reprehensible. Happily the trickery is generally distinguishable because the “dip” or stain, whatever it may be, is apt to run into the fringe or otherwise betray itself. The wise buyer will reject with scorn any rug, under whatsoever name offered, which shows no other colouring than various shades of chocolate brown. No such uniform brown dyeing ever characterized any class of rugs. Even the brown Bokharas which are in museums show some other tints with their brown tones.

Good Bokharas, like good Kirmans, are undeniably beautiful and of great value,[Pg 82] but the mere fact that both are considered staples in the rug trade tends to detract from their artistic value; and that they are so generally doctored, disguised, and perverted puts them in bad repute.

The Yamoud-Bokharas come in larger sizes than the others of their type; are not so fine in texture, but thicker and firmer. Their designs are larger and bolder, and they show a most becoming bloom. They also display green and even yellow in their colouring, which is not usual in Bokharas. Their selvedge is beautifully characteristic. In Bokharas proper the adornment of the selvedge usually is on the warp; as in the Bergamas and Beluchistans. In Yamouds the selvedge is almost always carried out in wool with like skill as that given to the rest of the piece.

The Afghans are a coarser edition of Bokharas, and may be mostly considered for utility. They come in large sizes, and almost square; have bold tile patternings, and in the finer examples are plush-like[Pg 83] and silky. These are still to be had, but many modern ones are dyed with mineral dyes, and their bloom is meretricious. The chemist has waved his magic wand over them, not wisely but too well.

The Beluchistans are somewhat akin to the Bokharas, and like the latter rejoice in reds and blues in the darker tones, while they display greater variety in their designs. These are ordinarily crude and simple, but in the old exemplars they were of considerable variety, and their wealth of changing colours in sombre shades was rich beyond the dream of avarice. “Lees of wine,” “dregs of wine,” “plum,” “claret,” “maroon,”—these are terms which have served to describe their prevailing colours. The adjectives are still applicable and may give some idea of the colourful effects which are obtained from their stains of brown and red and purple. For decorative effect, their deeper tones make most harmonious contrast with the subdued and softened Persians and old Daghestans. In[Pg 84] many specimens, new and old, white, both blue white and ivory, is used in startling contrast. It makes or mars the picture, according to the artistic skill of the weaver. The wool used in the good Beluchistans is particularly soft and silky, and lends to them their unique velvety sheen. No other varieties show it so perfectly, although antique Kazaks have their particular plush, and the Mousuls with their depth of pile have a shimmer and shifting light which is their especial artistic feature. The distinction may not easily be formulated; but, nevertheless, the sheen of the Beluchistan is one beauty, while the play of light and shade on a Mousul is another pleasure to the eye.

In the Bergama rugs the weaver does not disdain to spend some toil and time upon the selvedge; and this, even in small specimens, is commonly four to six inches long, carefully woven in white and colour and with occasional ornamentation. In this selvedge a small, elongated triangle is frequently embossed in wool, with the commendable purpose of avoiding the “evil eye.”

But in the Beluchistans the maker “enlarges his phylacteries, and increases the borders of his garments.” He goes even to greater pains and trouble in the elaboration and finishing of his selvedge. It is often prolonged to eight or ten inches in moderate-sized rugs, and is woven into most interesting patterns and stripes of colour. It is literally carried to extremes. It may seem an act of vandalism, but the wise and stoical collector will do well to eliminate all but two or three inches of it and have a skilful weaver overcast and fringe the ends. Selvedge, however adorned, is utilitarian only, and, like useless fringe, it must not be allowed to detract from the proportions and beauty of the piece itself.

For the comfort of the collector be it known that within the last year or two, many fine Beluchistan mats and small rugs have been secured somehow by the wholesalers and are in evidence in the retailers’ stock. Beluchistan, evidently, is one of the remote regions last to be drawn upon, scoured, ravaged, and exhausted. The opportunity should be improved by the provident buyer.

The Soumac or Cashmere rug calls for no further description than a Cashmere shawl. With the exception of choice antique specimens which time has chastened and mellowed into pictures in apricot, fawn, robin’s-egg, and cream colours, the Cashmeres are rather matters of fact than of art.

What are known as Killims, or Kiz-Killims, the better class, are hard fabrics akin to the Soumacs except that they have no nap on either side, and are double faced. They are mostly Caucasian and Kurdish, with the bold designs of those classes, or they come in the beautiful, delicate patterns of the Sehnas. In their crudest and strongest Kazak figures they[Pg 87] appear in the most brilliant pigments, with soft reds, rose, lake, and vermilion for contrasting colours, splashed together as on a painter’s palette. Of course they lack the sheen of a rug, but their colour effects are marvellous. While generally used for portières and coverings, they are perfect rugs for a summer cottage, being most durable, and are worthy of attention. Moreover, fine antique examples are still to be had. Some collector might be the first to make a specialty of them and garner them before they pass; the end of the Oriental weaver’s pageant. The usual warning, however, must be given, that they are often cursed with the barbarous magentas hereinbefore mentioned, a colour which would ruin a rainbow.

The products of Samarkand are quite out of the ordinary, and thoroughly Chinese in character. Except by association and classification they have no resemblance to the Turkestan or any other division. They form a class by themselves, the legitimate successors of the old Chinese rugs, long gone by. They are very bold in design, and in colour tend to yellow, orange, and various soft reds. An inferior make of Samarkands often appears under the title of Malgaras. They have neither quality nor colour to commend them.

But there are old Chinese rugs also. Most of them are in the conventional blue and white, with simple octagonal medallions, with no border to speak of, and with little strength of character. They are coarsely woven and have been so commonly imitated by machine reproductions in English carpetry that even blue and white originals have small merit to boast of. There were, and doubtless still are, Chinese rugs of far more importance. Many are noted in the catalogue of a sale in New York City no longer ago than 1893. From one item remembered, they showed various beautiful colourings, far beyond the simple white and blue, and in design displayed much of the[Pg 89] artistic strength, grace, and beauty of the old Chinese porcelains. It is a mystery where these rugs lie hidden. No one boasts of owning them or claims credit to even a modest $10,000 antique specimen.