Savouring Pleasures of Life with Turkish Carpets

Gorgeous Oriental carpets rank among the most alluring things that one can have in the personal collection, in the living room floor or hanged in the wall. However, choosing one of them can be a challenge. Such rugs can be compared to highly valuable ‘objets d’art’ like paintings or sculptures. Carpet weaving remains one of the most ancient ways for the expression of applied arts. The ideal way to buy an oriental rug would be to travel at the countries where they are made. Traveling to Iran, Afghanistan, the Caucasus region or Turkey would be the perfect way for learning more how these rugs are made.

Lucky are the persons who did this, because traveling to a region that is currently is going through difficult moments is not safe. For the moment, Turkey is one of the safest countries to travel. On the other hand, Turks are some of the most ancient carpet weavers. The area of Anatolia is strongly linked to carpets. The Turkish tribes that arrived in the area during the 11th century. The cities of Sivas, Konya and Kayseri turned into important centers of production and the rugs made were named after the name of these cities.

At first, these rugs presented floral and geometrical motifs and reflected tribal influences. Later, images of animals started to be included in carpets. Even though few rugs from that period remained, European painters from the Renaissance period included them in their paintings. In the 15th century, Anatolian carpets started to appear in renaissance art. The artworks of Lotto, Bellini, Holbein, Memling, Carpaccio and many others that were fascinated by oriental handicrafts served as perfect ways of documentation for the rugs imported from Turkey.

In the same period, the cities of Bergama and Usak or Oushak gained importance as weaving centers. Other carpets that were made at the area along with Kayseri, Konya Oushak, and Bergama are Milas, Sivas, Kula and Yuruk. Some of these are also recognized as Transylvanian rugs because they have been found in churches in Transylvania. Hereke is another area near Istanbul that was famous because of its exclusivity for the production of carpets for the Ottoman Sultans. Even though the time of Sultans faded long time ago, Hereke remains still one of the places where are weaved some of the finest rugs.

Carpet weaving is one of the oldest crafts in Turkey and the rugs produced in the country are highly wanted by interior decorators. They fit in every home design due to their nomadic origin, which makes it easy to pair patterns. Nomadic carpets rank among the most wanted oriental rugs.

Another important detail about Turkish rugs is that they have been mostly weaved by women. This fact is believed to explain the harmony of designs and patterns in Turkish rugs. Designs are chosen to be in harmony with each other, thus to create a language of expression. Each element is carefully selected in order to create the unity of the carpet. Women weavers consider their creations as poetry expressed in knots and motifs.

Currently, the rugs made in Turkey portray patterns that include medallions, flowers Safavid-Persian style arabesques and carefully chosen colors that can fit in every room. Prayer rugs or nomadic carpets, each of them will enlighten your house. Now that you know more about Turkish rugs, it will be easier to find one without traveling to Turkey and remember that you can never outfox a Turkish merchant of rugs.

OF TURKISH RUG VARIETIES

Chapter VII – The Oriental Rug by William De Lancey Ellwanger

BABYLON or Egypt may have woven the first carpets or floor coverings, and China of course worked early in the same field. But Persia acquired the art quite independent of China, and well in the beginning of the long ago. Indeed, the Chinese industry practically ceased to exist many centuries back, and was transferred to northern Persia, where the history of this handicraft has its true beginning. From Persia all other countries have drawn their knowledge and inspiration, and however much they may have endeavoured to create and to evolve new figures and new designs, even the oldest examples of their art must concede something to Persian influence.

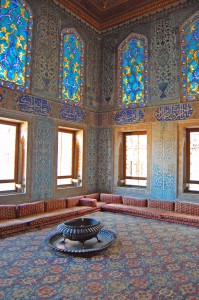

The Turks, above all others, have shown themselves the most apt scholars, and indeed in many lines have improved upon their teachers. The choicest specimens of Turkish weave are as rubies to the other precious stones, rarer, more brilliant, and more costly than diamonds. Though not so closely woven as some of the Persians, they are wonderfully beautiful in artistic picturing and in their own Oriental splendour of colour and design. Such in particular are the antique Gheordez, as splendid in rich floods of light as the stained-glass windows of a cathedral. They are the finest woven and have the shortest nap of their class.

Here is the description of one taken from a catalogue of twenty-five years ago:

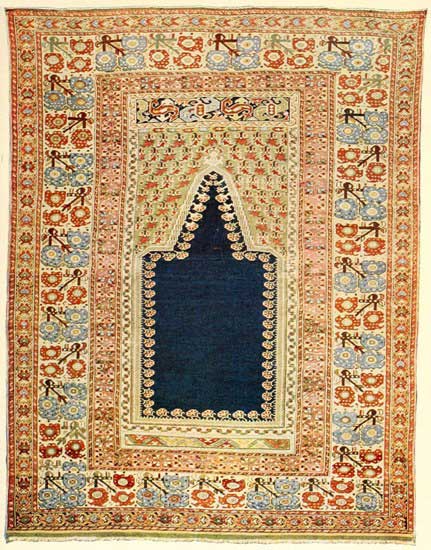

“Antique Gheordez Prayer Rug. Mosque design, with columns and pendant floral lamp relieved on solid ground of rare Egyptian red, surmounted by arabesques in white upon dark turquoise, framed in lovely contrasting borders.”

Prayer Rug

From the Collection of Mr. George H. Ellwanger

Size: 4.6 x 5.11

Another is pictured as:

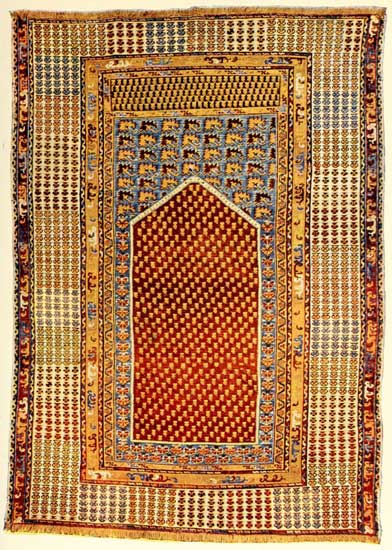

“A flake of solid sapphire, crested by charming floral designs in ruby on ground of white opal. The mosaics and blossom borders are toned to perfect harmony.”

These word pictures are in no way exaggerated, and only help to portray the glories of the old Gheordez, with their graceful hanging lamps, as wonderful as Aladdin’s, in a vista between pillars of chalcedony or onyx. They came in the form of prayer rugs generally, and a pronounced feature of those more commonly seen is a multiplicity of small dotted borders. The older and finer examples show borderings of far more graceful and artistic drawing.

The antique Koulahs and Koniahs, though not so finely woven, have mostly the same superb centres or panels of solid colour as the Gheordez, and vie with the latter in the splendour of their hues, if not in the delicacy and intricacy of their designs outside the central field. The Koulahs may generally be recognized by a narrow border, which is peculiar to themselves and is almost invariably found on them. This consists of a broken line of little tendrils or spirals quite Chinese in character, and looking much like a row of conventionalized chips and shavings. It is so odd and distinctive that once seen it can never be mistaken. The Koniahs also have little figures which are quite their own, and which usually appear somewhere in the central design. They are small flowers each on a single stem, and the flower has commonly three triangular petals, like an oxalis or shamrock leaf. It is quite unlike the blossoms which besprinkle other rugs. With this, often come crude figures of lamps like miniature tea-pots. The Ladiks display all the colours of an October wood, and complete the group of Turkish old masters. Not a few of them have also a unique border in the form of a small lily blossom. Experts speak of it familiarly as the “Rhodian border,” but its origin is altogether obscure.

Prayer Rug

From the Collection of Mr. George H. Ellwanger

These words in testimony to the beauties of Turkish rugs may be offered simply by way of guide-posts to lead to some museum. A few battered and torn war-flags of Gheordez or Ladiks are occasionally offered on the market, but the best of them lack all character and colour, and show only the bold design and holes and strings and naked warp.

Just which particular Turkish rugs are properly classed as Anatolians it is hard to say, Anatolia being so large a province. The term as commercially used is only as comprehensive and expressive as “Iran” applied to the Persians. It is generally misapplied to an uncertain class of old, worn, and tarnished remnants or new coarse prayer rugs, ruinous of harmony with their magenta discords. Yet many of the “mats” are rightly called Anatolians, and, premising a later chapter, one of the greatest delights of collecting was to look[Pg 74] over a pile of them, with the never-failing hope of finding some bright particular gem. And these mats are truly the little gems of Turkish weaving, and in accordance with the Oriental fondness for jewels and precious stones the suggestion that they represent inlaid jewelled work has been well imagined. But here again we cry, “Eheu fugaces!” They have gone. It is idle to look over the pile. There are no good ones for sale. One explanation of their scarcity is in the fact that the Armenian dealers have a weakness for these small pieces themselves, and are wont to indulge their fondness for colour and sheen by keeping the choice ones for their own use. So the mats of commerce are either new, coarse, and crude and offensive with arsenical greens and aniline crimsons and magentas; or they are but soiled patches and bits of old rugs sewn together. Caveat emptor! and let the buyer look at their backs before purchasing.

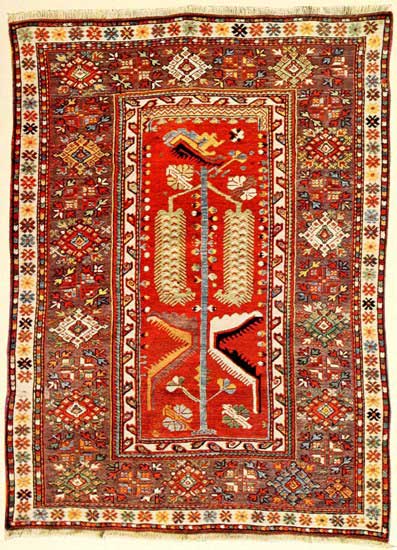

The old Melez rugs, with characteristics peculiar to themselves, are of almost like importance to the Koniahs and Koulahs. Frequently they have a suggestion of the Chinese in their figures and decorations. You will find symbolized dragons pictured on them, also the cypress tree; while in colour they form a class by themselves, and exhibit shades of lavender, heliotrope, and violet such as no other kinds may boast. Whatever this dye may be, and whatever tone of mauve or lilac it may take, you will find it only in the Melez, a few Bergamas, or in some old Irans, whose race is practically extinct. Worthy modern Melez are still to be had, and will improve as they wear; if only they are firm in texture and do not flaunt the battle-flag colours of Solferino and Magenta.

Forty or fifty years old

From the Collection of the Author

Size: 3.10 x 5.3

The Bergamas come mostly in blues and reds, most prominently set out by soft ivory white. One of their recognized patterns is quite individual, and readily marks their class. It is a square of small squares marked off like a big checker-board. Other small pieces are almost square, with the field in mosaic-work or flower blossoms. In the fine old specimens, which used to be, the Bergamas rioted in superb medallions or in a floriated central figure like a grand bouquet. As a class, their merit is softness and richness. Their defect is that of the Shiraz, a proneness to curl and puff themselves with pride. The fault is caused by the fact that their usually artistic selvedge is too tightly drawn. Skilful cutting of the selvedge and new fringing will correct the error.

Some old and some excellent new Bergamas have lately been in evidence in the stocks of the Oriental dealers. Howsoever or wheresoever they come, the collector may well take courage from their appearance and apply himself to the chase with renewed zest.